It’s a generational

thing, the radio

The audience for pop

music and, by connection – at least at one time – AM radio, seems to run in

cycles that last maybe five years or so. My time, when pop meant the most to me

and my radio, ran from 1964 to 1969, bursting out of the gate with I Want to Hold

Your Hand, ending with the embarrassing Sugar Sugar.

By 1978, pop had moved

on to a generation still in grade school while I was graduating college. It

made for a rough ride if you were trapped in a car with only an AM radio, or

hanging in a bar with a hit-bound jukebox as a soundtrack. It was an endless loop of Blue Bayou

and white people neutering Motown – anybody up for Rita Coolidge’s The

Way You Do The Things You Do? I didn’t think so. You Light Up My Life. Andy

Gibb. Chuck Mangione. Eric Clapton, light years from Cream, with the dreary

Wonderful Tonight. Copacabana. The Stars War Theme. The Wiz. Grease. Saturday Night

Fever.

Thankfully, as you get

older your horizons widen, as do your options. Albums and FM radio become the

coin of the realm. And while regular radio was no place to seek refuge, if you

looked hard enough, or were interested enough, 1978 was a pretty decent year.

Looking back with 40 years of hindsight, this was a hip Hackensackian’s top 40

for 1978.

1. Racing in the Streets (Bruce Springsteen)

2. Shot By Both Sides (Magazine)

3. Because the Night (Patti Smith)

4. Miss You (Rolling Stones)

5. Number One (Rutles)

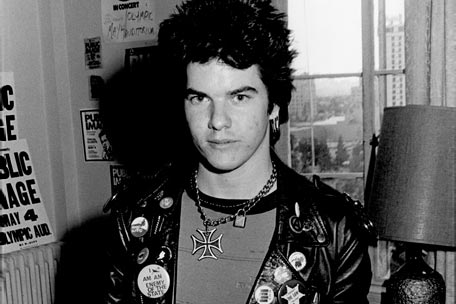

6. Public Image (Public Image Ltd)

7. Ca Plane Pour Moi (Plastic Bertrand)

8. I Need to Know (Tom Petty)

9. Pump It Up (Elvis Costello)

10. Jocko

Homo (Devo)

11. Senor

(Bob Dylan)

12. Take

Me To The River (Talking Heads)

13. Disco

Inferno (Trammps)

14. Lawyers

Guns and Money (Warren Zevon)

15. On

the Air (Peter Gabriel)

16. Badlands

(Bruce Springsteen)

17. Roxanne

(Police)

18. Don’t

Let Me Be Misunderstood (Santa Esmeralda)

19. Stay/The

Load Out (Jackson Browne)

20. Every

1s A Winner (Hot Chocolate)

21. I

Wanna Be Sedated (Ramones)

22. And

So It Goes (Nick Lowe)

23. The

Big Country (Talking Heads)

24. Navvy

(Pere Ubu)

25. David

Watts (Jam)

26. Good

Times Roll (Cars)

27. Look

Out For My Love (Neil Young)

28. Breakdown

(Tom Petty)

29. Hanging

on the Telephone (Blondie)

30. Punky

Reggae Party (Bob Marley)

31. Running

On Empty (Jackson Browne)

32. Prove

It All Night (Bruce Springsteen)

33. One

Nation Under A Groove (Funkadelic)

34. Sultans

of Swing (Dire Straits)

35. Baker

Street (Gerry Rafferty)

36. Love

Is Like Oxygen (Sweet)

37. Take

Me I’m Yours (Squeeze)

38. Wavelength

(Van Morrison)

39. FM

(Steely Dan)

40. Walk

And Don’t Look Back (Peter Tosh)